Definition and Prevalence

Northeastern University’s Office for University Equity and Compliance defines sexual assault as:

- Sexual contact and/or sexual intercourse that occurs without consent of all parties involved

- Non-consensual sexual contact: any intentional touching of a sexual nature performed by a person upon another person, without the consent of all parties involved, including the intentional touching of the intimate body parts of another—such as breasts, buttocks, groin, genitals, or the clothing covering them, or forcing or coercing another person touch you or themselves with or on someone’s breasts, buttocks, groin, genitals, or the clothing covering them.

- Non-consensual sexual intercourse: any oral, anal, or vaginal penetration, however slight, by an inanimate object, penis, or other bodily part without the consent of all parties involved; forcing or coercing another person to penetrate someone else; the attempted oral, anal, or vaginal penetration of an individual(s) by an inanimate object, penis, or other bodily part without the consent of all parties

involved.

Learn more from RAINN (Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network) about the scope of sexual violence experienced by college-aged adults and by children and teens. To see Northeastern specific data, please see Northeastern’s annual Survey on Sexual and Gender-Based Harassment.

If you have experienced sexual violence and are looking to understand more about the effects of trauma and ways to take care of yourself, check out OPEN’s guide: “We Believe You: Information on Trauma and Coping for Survivors of Sexual Violence.”

Common Reactions

Everyone copes with sexual violence a little bit differently. There is no one “right way” to feel or one standard route to healing after an experience of sexual violence. Each person will need to find what works for them. That said, many survivors find it helpful to know about some common reactions to sexual violence. These can include:

If you are experiencing some or all of these symptoms, know that you are not alone. Individual or group counseling can help in managing these symptoms.

If you are experiencing some or all of these symptoms, know that you are not alone. Individual or group counseling can help in managing these symptoms.

Sexual Trauma & The Brain

After experiencing sexual violence, it is not uncommon for survivors to question their own reactions, both during the traumatic event itself and/or afterwards. You might be asking yourself things like, “Why didn’t I fight back?” or “Why can I remember some details perfectly and others not at all?”

It can be easy to judge our reactions before we understand what’s happening in our brains that produces these very legitimate responses to experiencing trauma. While these reactions can be confusing and frustrating, it is important to remember that your brain’s response to what you have experienced is normal and is intended to protect you from further harm.

There are distinct parts of our brain that are used in different processes. The brain stem controls autonomic processes (i.e. breathing), while the midbrain deals with sensory info and emotional processing. The prefrontal cortex, or forebrain, is involved in decision making, planning, and problem solving.

When a traumatic event happens, our forebrain goes “offline” and the instinctive and emotional parts take over. Therefore, how we react when a traumatic event occurs may not be how we would expect to react if we were able to exercise our conscious control. Instead, our reactions are managed by the other parts of our brain so that we can survive the experience.

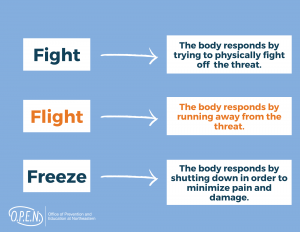

Our brains do the best job they can to keep us safe. The brain’s reaction to trauma allows the body to respond in several different ways:

There is a pervasive cultural perception that someone who is being assaulted would naturally fight back. However, the reality is that it is not typical for the brain to choose this option when a traumatic event occurs. It is far more typical for someone experiencing a sexual assault to freeze up once the brain detects a serious threat to rest of the system. Because our prefrontal cortex, or the part of the brain that makes decisions and engages in problem solving, is “offline” during an assault, we may not react in a way we would expect.

There is a pervasive cultural perception that someone who is being assaulted would naturally fight back. However, the reality is that it is not typical for the brain to choose this option when a traumatic event occurs. It is far more typical for someone experiencing a sexual assault to freeze up once the brain detects a serious threat to rest of the system. Because our prefrontal cortex, or the part of the brain that makes decisions and engages in problem solving, is “offline” during an assault, we may not react in a way we would expect.

Additionally, once the limbic system in the midbrain is activated during an assault, a neural shortcut to that area emerges that causes the brain to remain mobilized and hyper-aware of cues that remind us of the traumatic event. When we respond to these cues (sights, sounds, smells, etc.), also known as triggers, it can feel as if the assault is happening in real time.

Books like The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk, M.D. or Trauma and Recovery by Judith Herman may be helpful resources in understanding more about how trauma impacts the brain and body, and about how people recover from trauma.

Supporting a Friend

If someone comes to you and discloses that something happened to them, know that it probably took a lot of courage for them to do so. You can learn more about how to support a friend or loved one who has experienced sexual assault by taking our Canvas course titled RESPOND: Trauma-informed Response to Disclosures of Sexual Violence.

Here are some things to keep in mind:

During a Disclosure

If it’s an acute situation, ask if they are safe and/ or need medical attention. Do your best to help them get to a safe place. Learn more about immediate steps here.

Believe, validate and listen non-judgmentally. “I’m so sorry that happened.” “I believe you.” “I know you know this, but it’s not your fault.” Shame is a common reaction to sexual assault. Many survivors worry that people they tell will not take what they say seriously, think it’s not “that bad,” or will blame them for what happened. Validating their responses will help to ease anxiety they might have about this.

Don’t expect all the details. For people who have experienced trauma, it is often not helpful to recount every detail. Even though you might be curious, avoid asking them to share the whole story unless they want to tell it. “You can share as much or as little as you want to.”

Mirror the language they use. Use whatever language they use instead of labeling the incident(s) yourself. For example, if they say, I was “assaulted,” don’t use the word “raped.”

Avoid questions that could feel blaming. Often we ask questions to show our care or interest. In this case, sometimes questions can imply blame. Avoid questions like, “Where were you?” “Why were you there?” “Were you drinking?” “How did this happen?”

Respect your friend’s power and choice. Avoid saying things like “You should go to counseling” or “You should make a report.” Instead, try to get a sense of what the person wants and needs. You might say, “What do you need right now?” or “What would be helpful?”

Be mindful that physical touch may not be helpful for your friend. Every survivor is different but many find that especially right after an assault, they do not wish to be touched even by friends. Ask if it’s okay to give them a hug or to put a hand on their shoulder. “Can I give you a hug?”

Educate yourself in order to support them. Learning about common reactions to trauma might help you to normalize what’s going on for them. They may not want to do some things they used to like doing at least for a little while. For example, they may not want to go to parties or be in large crowds. They might have a lot of trouble sleeping and be frequently tired. Healing is a process that will take time.

Refer them to professional support. Familiarize yourself with campus resources so that you can help refer them when they are ready. Remember that you do not need to be their counselor or sole support. If you need help deciding how to best support your friend, staff at the Sexual Violence Resource Center can meet with you to discuss.

After a Disclosure

Don’t treat them very differently. Remember they are a whole person. This one incident does not define who they are. Don’t pity them or bring every conversation back to this. Some sense of normalcy will be healthy. Continue to invite them to do the things you enjoyed doing together.

Create a follow up plan. It may be hurtful to your friend if you bring up what happened all the time or never again. Avoid saying things like- “Don’t worry we never have to talk about it again.” Rather you can ask- “Would it be okay if I checked in with you about this from time to time?” “What would be helpful from me going forward? I’m always here whenever you want to talk about it.”

Respect their privacy. It’s really important that they get to decide who to tell and when to tell them. Don’t tell others, especially in your same social networks.

Take care of yourself! Family and friends may react to the sexual assault of a loved one with many of the same feelings and physical reactions that the survivor experiences. Initially you may respond with shock and disbelief, feel intense fear for your or the survivor’s safety, feel anger towards the attacker, feel depressed and powerless, or feel guilty that you could not prevent what happened. All these feelings are normal reactions, but it can be helpful to meet with a counselor to share what you are feeling. Even if you choose not to meet with a professional, be sure to get support for yourself, whether from friends, family, a partner, or a mentor. If you are a Northeastern community member looking to learn more about how to support someone impacted by sexual violence, you can connect with OPEN’s confidential Community Consultation services by filling out this service request form.